Stephen Saunders

This post is based on the research paper, ‘Why do we have a big Australia’?

Pruning migration is low-hanging policy fruit compared with reducing greenhouse emissions.

Bill Shorten wrote to Scott Morrison recently proposing a “bipartisan approach” to population policy not the “politics of division”. In my jaded interpretation, he meant: Let’s not budge on Big Australia. Instead, let’s keep making unattainable promises on infrastructure and decentralisation.

Is Australia’s high population growth a logical fixture, endorsed by all, for the good of all? Tilting at these assumptions is the Australian Population Research Institute’s Report Why do we have a ‘big Australia’?, released last month.

I define big Australia as an inordinate appeal to high migration and high population growth, as headline and future economic tools, with larger regard for GDP growth and smaller regard for the environmental and social consequences.

Put that way, no such program could have emerged in the aftermath of World War II. The global ascent of GDP was in its infancy. Neoliberalism was decades away. Rather, defence and development guided Arthur Calwell’s pro-Briton “populate or perish” program. He wanted 2 per cent population growth; half would be natural increase, half immigration.

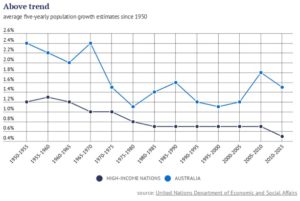

Higher population growth accompanied the 1950s boom in Australia. From the 1970s to the 1990s, net overseas migration dipped; it averaged less than 100,000 a year. Population only grew about 1 per cent a year. But GDP growth, though volatile, was commonly 3 to 5 per cent. It was a period of economic reform.

From 2000, however, John Howard decided to crank up immigration. By 2005, the mining boom was being used to justify this surge. Howard and then Opposition Leader Kim Beazley clicked as self-described “high-immigration men”.

In effect, the Gillard government’s A sustainable population strategy for Australia, released in 2011, rubber-stamped Howard’s policy shift. The official migration intake is now off its peak of 190,000. But net overseas migration is still running well over 200,000, a level never attained before 2007. Population growth is 1.5 per cent and more. That’s much higher than most rich OECD nations – or even India.

This record population growth is largely removed from the party-political contest. But public opinion has shifted in recent years. Various polls (TAPRI, Essential, Newspoll, even this year’s Lowy) now find 54 per cent or much higher majorities that favour lowering immigration or population growth. A couple of polls still find for a (very substantial) minority instead.

If the will of the people was ever going to count, why not on the number of migrants? Or, should the people defer to those in the growth lobby, who are confident they know better?

And who is in the growth lobby anyway? Most of the influential interest groups you can think of – except the electorate.

The groupthink begins with the three main political parties. With varying emphases, all celebrate Big Australia for its “jobs and growth” and “multiculturalism” or rejection of racism. Professed public interest motivations also apply to academics and professionals, and to unions, social or religious organisations.

The vaunted multiculturalism has its own racial signatures. India and China have now overtaken Britain as our top migration nations, but significant constitutional and policy arrangements remain decidedly pro-British or pro-Christian. Politicians launch incendiaries against refugees and “African” or “Muslim” immigration, though all three groups are statistically small segments.

The European migrant cultures are more respected now, lionised even. For the original Indigenous Australians, however, respect is a sometime thing. There are the gains of land rights and native title. Against that are high incarceration rates, remote work-for-the-dole schemes and cashless welfare cards. The Indigenous consensus on constitutional recognition was rejected out of hand.

By default, the Treasury is our key population agency. To help perpetuate the 27-year “miracle” in GDP growth, it quietly limns each Budget with high net overseas migration and high population growth.The Reserve Bank, unlike the Productivity Commission, pushes the supposed demographic rejuvenation from high migration. Well over half of all migrants, and well over three-quarters of skilled migrants, go straight to Sydney or Melbourne. The RBA, however, suggests that “zoning restrictions” push up city house prices.

This post originally appeared as an article in The Canberra Times,

6 November 2018