Katharine Betts

13 June 2016

For the past ten years Australians have been subjected to an exceptionally high level of population growth and now they are losing patience.

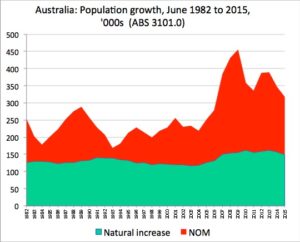

The graph shows the steep increase in numbers since 2006 (data from here). If this continues the population will grow from 24 million today to around 41 million in 2061 (see the 2013 ABS projection series 29 and 41).

In November 2015 a survey commissioned by Sustainable Population Australia (SPA) found that 51% of voters thought Australia did not need more people. Then in May this year a survey done for SBS TV found that 59% of people thought that the level of immigration over the last 10 years had been too high.

The SPA survey asked respondents to give reasons for their opinion. Many of those who thought we did not need more people said our cites were overcrowded (with too much traffic)—consequences of rapid growth all too apparent to urbanites. Others spoke of job competition. And many worried about the effects of growth on Australia’s fragile environment. Concern about too much cultural diversity and migrant enclaves was also high on the list.

The SBS survey focused on immigration and found that dissatisfaction with immigration was even higher than with growth in general. It asked about multiculturalism and 46% of respondents said that this had failed. It had brought social division and religious extremism to Australia (43% of those who were immigrants themselves agreed).

It was reasonable for SBS to focus on immigration because this accounts for the major part of the current population boom — around 58%.

Immigration is a product of government policy. It’s the outcome of decisions made by political elites, prompted by lobbyists for property developers, employers, and other businesses that profit from population growth. The two surveys show that the electorate is fed up with the unwanted growth that this power elite has wished upon them.

The record numbers of migrants in the 2000s were partly justified by the push to keep affordable skills coming during the investment phase of the resources boom. But since 2012 that justification has evaporated and economic growth has slowed. Despite this, Governments, both Labor and Coalition, have kept immigration high. Now the motivation is to keep the housing and development interests happy. They continue to profit from a stream of new customers, a stream which also keeps the construction industry going and creates the appearance of a busy economy. But this strategy has not increased per capita income. Quite the reverse.

It’s not just that forced population growth leads to clogged infrastructure, cultural disruption and environmental deterioration, it is also comes with financial stress.

Leith Van Onselen writes that:

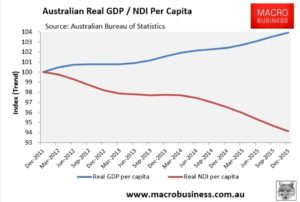

While headline GDP growth across Australia has held-up reasonably well over the past decade, thanks to high immigration, per capita real GDP is trending down so sharply that it has fallen to levels not seen since the early-1980s recession. …

While real GDP has been rising since December 2011, net disposable income (NDI) per capita has been falling. See graph below. (NDI is explained here.)

Urban voters are also angry about the level of densification forced on them by undemocratic planning authorities determined to accommodate developers. Groups such as Planning Backlash, BRAG (Boroondara Residents Action Group), Save our Suburbs, RAGE (Residents against Greedy Enterprise) and the Carlton Residents Association all express deep frustration about over-development, loss of heritage and declining quality of life.

So far the growth lobby has been able to keep on profiting from ballooning numbers, partly because few voters fully understand what is being done to them. They know that conditions are getting worse but they don’t fully understand the key role played by population growth.

The SPA survey tested respondents’ knowledge of demographic change. The minority (16%) who had a good understanding were the most likely to say that Australia does not need more people. But 82% knew very little. Though they were unhappy about time-devouring traffic jams and ugly new high-rise apartments, they didn’t always know why these miseries were being wished upon them, or why they felt so powerless.

But their unhappiness has political effects, effects which can explain why governments have been toppling so fast. Kelvin Thomson calls this the witches hat theory of why governments fail. Mark O’Connor summarises it thus:

[S]taying in power, and keeping the electorate happy is a little like an advanced driving course, one in which a government is required to thread a kind of slalom course between a series of witches’ hats — meaning the orange inverted cones that mark out the course. These hats, which the government, like the driver, needs to avoid knocking over, include such things as keeping electricity and water costs down, reducing hospital queues, keeping housing affordable, preserving the environment, providing full employment, restricting inflation, etc.

And the faster a country’s population is rising, the harder it is to do this… It’s like trying to negotiate the course at double speed.

As Thomson himself puts it:

[W]hen politicians … look in the mirror and ask ‘Why don’t they like me?’, the answer might well be that they are driving the car too fast and knocking over those witches’ hats. They should slow the car down and focus on solving people’s real-life problems.

It is not surprising that Dick Smith, outspoken critic of mindless population growth, is now the most trusted public figure in Australia. Or that mainstream politicians are among the least trusted.

An op-ed piece based on this blog was published under the title ‘Exceptional rates of population growth are causing stress on many fronts’ on 22 June 2016. It appeared in The Canberra Times, The Age, and The Sydney Morning Herald.

Thanks for finally talking about >Population growth, polls and politics – The Australian Population Research Institute <Liked it!