Bob Birrell, Migrant deluge creates a giant wave of problems

This article was first published in The Herald Sun, 30 September 202

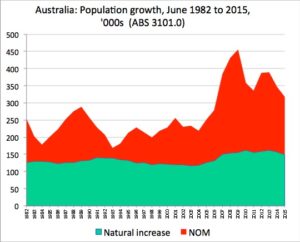

In 2022-23 Australia’s net overseas migration (NOM) is expected to reach 450,000. This is way above the level before Covid of about 250,000. If there are no policy changes this huge influx will continue. We know this is the case because it is largely based on a sharp increase in the number of overseas students and visitors (more on this category shortly). The number of overseas students already in Australia is a record. So is the number of new student visas issued in 2022-23, most of these were issued offshore and are still to move here.

The recruitment of overseas students has built up a head of steam that, if not capped, will generate massive further increases. Most of these students are in the higher education sector, where universities are actively seeking more because of the financial incentives. However, though from a lower base, the numbers visaed in the cheaper English Language and vocational colleges is exploding. This is because these courses offer a much cheaper entry point into our labour market.

Student visas are crucial because they provide a legal right to work here while studying. Once here students can move from one temporary visa to another, thus prolonging their time in our workforce.

A similar process applies to those arriving on a visitor’s visa. Their numbers, as noted, have also surged. A visitor visa offers an easier and less expensive pathway to Australia. Huge numbers are now using this pathway to stay on, mostly on a student visa which they obtain after they have arrived. In 2022-23, some 75,000 visitors were granted a student visa. This number is unprecedented.

The migrant deluge was not official Labor Government policy. It is an unplanned outcome. Once Covid period restrictions on visaing temporary entrants and travel restrictions were removed, Labor put no constraints in place. It just let the recruiting process rip. The subsequent influx reflects a monumental failure to anticipate the response.

Worse, Labor facilitated the deluge by throwing financial resources at slashing delays in processing visas. It also left the flimsy academic and language requirements and weak financial capacity regulations in place. As long as students have the funds to pay their up-front first year fees, there are minimal requirements on proof that they have enough funds for their subsequent fees and expenses. Decisions on these standards have been left to the universities, who do not have an interest in taking a tough line.

The Government’s failure to anticipate the subsequent migrant deluge is illustrated in spades by the forecasting record of its Office of Population located within The Treasury. In December 2022 the Office projected that NOM for Australia would be 235,000 in 2022-23. Just five months later at the time of the May Budget, the Office adjusted its forecast to 421,000. In fact, as indicated, it is likely to be around 450,000. The Office projects that NOM will reach 350,000 in 2023-24 and 300,000 in 2024-25. This, too, is likely to be an underestimate unless the Government acts to get the recruitment process under control.

Labor has shown no signs of doing so. Quite the contrary.

The Government has flagged its intention to integrate overseas students into our skilled labour workforce. It will do so by creating an easier pathway to a permanent entry visa for those deemed to have skills in short supply. Such promises just add to the inducements for overseas students to enroll in Australia. Also, from July 2023, overseas students who graduate in all fields of science, IT, engineering and health (including nursing) will be allowed to stay on in Australia for at least another two years. (This is on top of the existing minimum two years that university graduates from overseas can remain in Australia.)

Why worry?

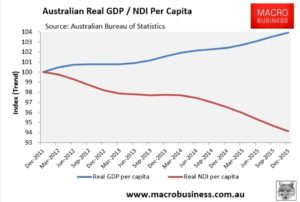

First, the sheer numbers of extra people are adding obvious pressure to Australia’s housing affordability crisis, especially rental accommodation. This at its most serious in Sydney and Melbourne, where most recent migrants on temporary visa are moving to. They do so because that is where the overseas student industry is predominantly located.

Second, Labor’s policies of directing overseas student graduates into Australia’s skilled workforce is having serious consequences for domestic students’ opportunities. It is far more lucrative for universities to enroll overseas students than domestic students. Already, our universities graduate many more overseas students than domestic students in engineering and IT. Labor’s new policy of encouraging even more overseas students to enroll in the sciences will prompt our universities to devote more of their teaching capacity in these fields to overseas students. Nursing is likely to be a growth point, again because it is far more lucrative to devote any extra capacity for nurse training to overseas students. This will be at the expense of opportunities for young Australians.

Bob Birrell is the head of The Australian Population Research Institute