Stephen Saunders

By no means did the 2019 federal election arrest our radical immigration economy. The Coalition was set to crank it higher. Labor and Greens would have gone higher again.

In calendar year 2017, net overseas migration to Australia was nearly 242,000. The preliminary tally for 2018 climbs to 248,000.

Now the Treasury is ‘assuming’ net migration to top 270,000 in 2019 and 2020. Yet permanent migration is dropping by 30,000, to 160,000. This apparent contradiction is partly explained by the liberal use of bridging visas.

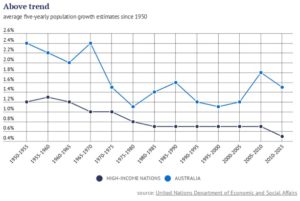

The long haul is the biggest story. Once only since federation has Australia surpassed 270,000 in net migration. Before 2007, even 200,000 was unknown. How come the figures have gone so high? Why are they barely remarked? And should we stay the course.

High population growth is at the behest of ‘GDP growth’

Technically, net migration is a mouthful. It’s those arriving in Australia and staying (by whatever visa) for 12 months out of 16, less those (who are resident and) leave for 12/16.

This imperfect measure is the best gauge available for the ongoing ‘mass’ of overseas arrivals. Nowadays, the net student arrivals swamp the net permanent arrivals. Net student arrivals also outnumber the net arrivals of temp-workers plus visitors. But note, about half of each year’s permanent-migrant tally is already onshore, on student or other visas.

In Treasury estimates, natural increase plus net migration equals population growth. Population is set to grow 1.7 per cent in 2019 and 2020, mostly from net migration.

These estimates appear as Appendix A ‘parameters’ in Budget paper no. 3. Australia’s natural increase, births minus deaths, is fairly low and predictable. The cursory explanation in the appendix is unobjectionable, though some may query the projected rise in fertility.

More problematic is the non-explanation of net migration. This setting has a signal effect on voters’ lives and effectively underwrites our high population growth. The appendix merely notes that the population ‘estimates’ hinge on the net migration ‘assumptions’.

In another sense, it’s no real surprise, if the appendix is uncommunicative. As above, the three main parties are rusted on to mass migration. The Treasurer and Treasury are under no pressure to explain themselves to the public.

Sure, the Budget migration ‘assumptions’ are roughly related to more recent trends. Even then, they’re higher than any actual outcome recorded ever since 2009. Why would Treasury vault the 2019 and 2020 assumptions another 20,000-30,000 above the large and unsustainable 2017 and 2018 outcomes? The Budget papers make no effort to clarify. Yet the answer can be in no doubt. It’s at the behest of the GDP statistic.

Over this past decade, population growth has underpinned more than half of our real GDP growth. The 2018-19 budget prescribed 1.6 per cent population growth for 3 per cent GDP growth. Budget 2019-20 downgraded the 3 per cent, to 2.25 per cent. It seeks 1.7 per cent population growth. This is for 2.75 per cent GDP growth. Which looks unlikely.

Perennially, Treasury is forecasting resurgent GDP growth. It’s not happening. More reliably, population growth powers whatever GDP growth we do get. That’s why Treasury migration and population estimates are so high. ‘GDP growth’ will have it no other way.

GDP growth is a tolerable measure to begin with, perhaps, in the advanced OECD nations with stable or slow growing populations. Such nations express little interest in imitating the continuing ‘miracle’ of our mass-migration economy. More appealing is the mystique of our migrant Points Test. Which doesn’t really select for skills in demand. Or the mystique of our Strong Borders. Which shutter the sea-lanes, yes, but not the air-lanes.

Measures like real GDP per capita, real wages per capita, and real wealth per household, begin to paint a more realistic picture of the Australian economy as it is experienced by ordinary people. The rich are getting richer as home ownership craters.

While the Budget cashes in its pro forma GDP gains, the Australian states carry the real-world infrastructure and service burdens of steeply rising population. Budget 2019-20 promised a sweetener of ‘$100 billion’ in infrastructure and ‘congestion busting’ over 10 years. Even if it were to be fully realised, still, it’s not enough.

A dominating lobby demands extremely high migration

New Zealanders measure and discuss migration in terms of net migration. Thus we can gauge readily that Labour isn’t meeting its clear 2017 commitment to cut migration.

By contrast, Australian politicians contest permanent and temporary migration, especially the relatively small humanitarian (or refugee) intake. Net migration is not on the agenda.

Again, the Budgets set the tone. Usually, Budget papers 1-3 avoid the population issue. Their spotlight is on jobs and growth, and the deficit or surplus. As discussed above, the so-called net migration and population ‘parameters’ tiptoe into their appendix.

Budget 2019-20 changed tack somewhat. Upfront, the Treasurer highlighted the Prime Minister’s new population plan (the Plan) and its permanent migration ‘cap’ of 160,000. But, in postwar terms, even that is an extremely high number 1. While the number that really matters is net migration, topping 270,000 in Appendix A.

In Budget Reply, Labor could have reasoned, you won’t ever cure congestion, with a mass-migration medicine. Quite the contrary. They were keen to up the dose.

With Greens support, they comprehensively outbid the Coalition on migration, promising virtually open-ended migrant-parent visas. Which could only have led to much higher net migration. As it transpired, voters weren’t buying. Not even in the obvious metro (Labor) seats with higher concentrations of migrant voters.

Reflect on the happy implications for the returned government. Opposition telegraphs to government a very wide discretion on migration and population policy. But the government can likely elicit an opposition response, if mooting changes to refugee and asylum policy.

An analogous point applies to the mainstream media. They scrutinise refugee policy more diligently than migration policy. When the budget was released, generally, the media recycled the budget highlights and migration cap. Rare was the reporter who would write up the migration blowout lurking beneath the cap.

At a societal level, in advanced OECD nations, so-called left-modernism discourages the open discussion of immigration and population. In Australia, the cross-party cheer squad for high migration unites political parties, state and city governments, developers, media, academics, and unions. The Treasury assumptions sync with this Big Australia lobby.

Less enfranchised parties calling for lower migration and population are the electorate (in repeated surveys) and the environment (in repeated State of the environment reports).

High population growth is both obsessive yet intentional

The government wouldn’t presume to supervise natural increase. As above, it is in any case fairly low and predictable. But the government does supervise net migration. And thereby supervises our turbo-charged (by OECD norms) population growth.

Let’s look at the current ‘Appendix A’ presentation, which debuted in 2009. Up to 2017, budget-night migration and population estimates (carrying time lags of some months in available data) may be compared with end-of-year outcomes.

Over this period, assumed net migration 2 ranges from 175,000 to 246,000. Actuals 3 seesaw between 169,000 and 264,000. The average annual error of the estimates is 40,000 plus, or 20 per cent plus. Estimated population growth varies from 1.5 to 1.8 per cent. Actuals 4 range from 1.4 to 2.0 per cent. Average annual error grazes 0.2 per cent.

Comparing the budget-night estimates to the end-of-following year outcomes, assumed migration varies from 180,000 to 250,000. Average error is under 20 per cent. Estimated population growth runs from 1.4 to 1.8 per cent. The average error just tops 0.2 per cent.

The Department of Home Affairs, it is to be noted here, carries onerous duties to manage diverse visas and their long queues. It has no control over people’s movements out of Australia. Also, it lacks real-time net migration data.

Despite the daunting logistics, Home Affairs is landing the short-run Treasury migration estimates with quite passable accuracy. Yet the common assessment is that visa processing is reprehensibly ‘chaotic’ or ‘out of control’. To the extent that this is true, wouldn’t you think about lowering migration, to relieve the pressure? Not in Labor or ‘progressive’ circles.

Turning now to the long term, here also, we manage our population. It’s not an accident.

Sure, at 25 million, already we’ve busted the 1998 ABS population forecast for 2051. But those extras didn’t fall from the clouds like rain. Repeatedly, our sovereign government has accelerated net migration, counting GDP gains and largely discounting collateral costs.

Former Prime Minister John Howard and former Opposition Leader Kim Beazley were me-too high immigration men. The latter, during the mining boom, readily acquiesced to ballooning permanent migration and steeply rising 457 visas.

By way of thanks, the miners gelignited Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s 2010 tax on super-profits. Their boom damaged our overall competitiveness. In a Coalition phase pre GFC, and Labor-Coalition phase post GFC, we’ve hugely increased overseas student numbers and deregulated visa pathways. At cost to systemic quality and local aspirants.

So it’s not that ABS couldn’t do the maths. The government decisively upped the population momentum. Our average net migration over 2007-2017 — at 220,000 plus — considerably exceeds two multiples of the quarter-century net migration average up to 2006.

With overseas-student numbers possibly peaking, how could net migration ever top 270,000? One analyst has suggested this would rely on a strengthening economy, plus extra chip-ins from working holiday makers, visitors changing status, and the new temporary parent visa. Once again, so much for the spin, around migration and skills in demand.

On the other hand, net migration might slump, should the economy weaken. But we’ve trumped 170,000 net, every year since 2006. To bolster migration and ‘jobs and growth’, the government could speed up visa processing, tweak visa rules or categories, intensify student drives in India or other markets, or unleash the migrant-parent visas.

Through to 2018-19, Australia trumpets ‘28 years of uninterrupted economic growth’. Surfing on net migration, the government and the Treasury may yet ballyhoo 30. Ordinary households and wage-earners would be left wondering, did they really ‘burn’ for us?

For the long term, the Treasury Intergenerational report assumes 215,000 annual net migration. Again, this is more than twice the average over 1982-2006.

Similarly, today’s ‘illustrative’ ABS projections will admit of nothing but high migration, at levels of 175,000 (call this, lower high), 225,000 (medium high) or 275,000 (very high).

In effect, the Budget is adopting the ‘very high’ ABS option. The Plan, meanwhile, hews to the ‘medium high’ ABS option. Even under these assumptions, Australia’s population would top 37 million, around 2050. By which time Sydney and Melbourne might hit 8 million.

To complete what is a less-than-virtuous circle, governments (notably their urban and transport planners) like to pretend that these brimming ABS numbers are ‘independent’ projections that will need to be accommodated.

Breaking ranks momentarily, even the NSW Premier briefly espoused a ‘breather’ of halving migration into NSW. She had a point. Once again, if you honestly want to ‘bust congestion’, you wouldn’t start off with full-throttle migration, pouring into Sydney and Melbourne.

Routinely, governments declare, we’ve got a fix, for these self-inflicted crushes. Behold then the Alan Tudge scheme to channel booming population away from big cities. Finally now, our stressed infrastructure will be able to ‘catch up’. Postwar history undermines such claims. As government itself says, few nations are so urbanised. An unyielding 40 per cent of the population occupies two sprawling and increasingly unequal cities.

When taken as normal, a 37 million in Australia by 2050 skates around unsustainable land clearing, habitat loss, water consumption, and greenhouse emissions. Yet the official Sydney and Melbourne urban plans both take as read a future 8 million. These ‘vibrant’ mega-city vistas are geared to elite economic interests. Not to the ordinary people.

Never mind the Canberra bubble. Focus on the population bubble. As government prolongs it, so also they prolong the implausible ‘congestion busting’ and ‘decentralisation’ fixes. Thus might they perpetuate our houses and holes (consumption and extractive) economy and its iron-coal-and-students trade. Net migration would better serve the national interest and the voter preferences, if managed at more like its 1980s-1990s levels.

In conclusion

Net migration, the Treasury population lever, is adjusted with little explanation or scrutiny. 21st century government has more than doubled it. Political parties defend this as normal:

* Though the permanent migration ‘cap’ would eventually bite into the migration ‘net’, the latter remains the best year-on-year measure of our true migration levels.

* The net migration tally renders more visible the habitual boosts to immigration, not for the welfare of residents, but for the sake of ‘GDP growth’ and the Big Australia lobby.

* Treasury’s high-migration assumptions scaffold this GDP growth. Dismissing environmental cautions, ratcheting population continues to prop up sputtering GDP.

* Net migration is geared to 270,000, a high exceeded once before, with population growth at 1.7 per cent, last observed in 2013. It makes a mockery of ‘congestion busting’.

* The true migration and population plans, despite their importance to voters, are by party consent absent from politics. Thus, they default to the Treasurer and Treasury.

* Post-election, Labor continues to brand as a high-migration party, contesting if anything refugee and asylum policy. Not every commentator can fathom the electoral logic of this.

Stephen Saunders (stephen@saunders.net) is a former APS public servant and consultant. A brief version of this article has appeared on Independent Australia. Thanks to Bob Birrell for the original idea and for the comments on this version.

1 It is like catnip to ‘progressive’ commentators to eagerly accept the spin that 160,000 permanent migrants is a sizeable reduction. Again, it’s net migration that matters. Also, if you’ve just had a decade of record high permanent migration, you don’t have to try very hard, to induce a ‘10 year low’ the following year.

2 Net migration and population estimates to 2017 are from Appendix A (B for 2011) of Budget paper no. 3 in Archive of budgets at https://archive.budget.gov.au. Annual percentage population growth estimates are no longer published, as they ought to be. The reader must compute them, from published population estimates.

3 Net migration for 2018 is available as a preliminary figure. Net migration (final) for the years 2009-2017 is read, from each following December’s ABS 3101.0, Australian demographic statistics. The December 2018 issue, now containing the final migration figure for the year 2017, was only released in June 2019.

4 Annual percentage population growth for the years 2009 through 2017 is read from each December’s ABS 3101.0. The figure for 2011 is adjusted here.

Katharine Betts was joint-editor of the demographic journal People and Place from 1993 to 2010 and has written widely on demographic topics. She is currently adjunct associate professor of sociology at Swinburne and vice-president of the

Katharine Betts was joint-editor of the demographic journal People and Place from 1993 to 2010 and has written widely on demographic topics. She is currently adjunct associate professor of sociology at Swinburne and vice-president of the